Nose, olfaction and fragrance: giving a sense to smell

This article was originally published in L'Édition n°25.

Long misunderstood, then unfairly ignored, the sense of smell generated renewed public interest during the Covid-19 pandemic. And yet, scientists from a wide range of fields have been studying this very subject for many years now. Researchers from Université Paris-Saclay reveal their approaches and recent discoveries in this area.

"What do you call someone who cannot see? Someone who cannot hear? And someone who cannot smell?" It was with these three questions that Claire de March, CNRS Researcher at the Institute of the Chemistry of Natural Substances (ICSN – Univ. Paris-Saclay/CNRS), started most of her lectures until recently. It was a way for her to prove that, while the terms "blind" and "deaf" are often familiar, the notions of anosmia (loss of sense of smell) and olfaction are far less familiar to the general public.

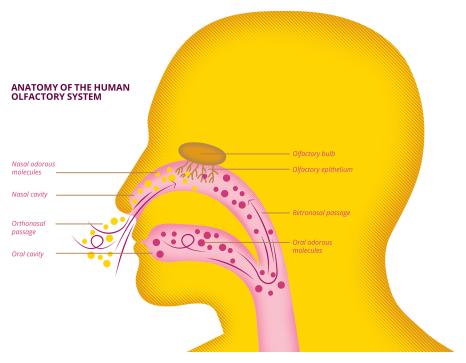

Studies dedicated to the sense of smell are relatively recent; the discovery of olfactory receptors, i.e. the structures that enable most mammals to smell, dates back only to 1991. "More than 20 years after Man walked on the Moon!" says Claire de March. The scientific community now estimates that the human nose is made up of around 400 different olfactory receptors, capable, by creating multiple combinations, of smelling between ten thousand and one trillion (one billion billion) different odours. Activated olfactory receptors create an electrical signal that stimulates olfactory neurons, which transmit the signal to the brain. The brain then interprets it as a scent.

The first experimental structure of a human olfactory receptor

What does a human olfactory receptor look like? This is the question Claire de March has been trying to answer for several years. After initial experience in sensory analysis in the agri-food sector, the researcher specialised in molecular chemistry in 2012 and decided to dedicate her research to studying the general functioning of the olfactory system.

It was during her post-doctoral programme in the United States that Claire de March quickly realised the limitations of biochemical studies on olfaction. The problem was the instability and insufficient expression of olfactory receptors in the cellular models used in the laboratory. This made it impossible for scientists to study the structure of these receptors and precisely measure their interactions with odorant molecules. Furthermore, some theoretical model receptors used for olfaction studies were still inspired by light receptors - involved in vision - which, although very different, are more easily expressed and cloned in the laboratory.

To overcome these experimental limitations, Claire de March proposed applying consensus theory to olfactory receptors. "This theory suggests that the amino acid most frequently present in a protein subfamily is the one that optimises its function, rather than a randomly selected amino acid," explains the researcher. In other words, the fact that an amino acid is often present in a protein sequence would mean that this amino acid is useful to the protein.

Based on this theory, Claire de March and her team selected all the amino acids most frequently present in olfactory receptors to recreate "consensus" olfactory receptors, which do not exist in the human nose but are comparable to ancestral receptors from which all other receptors would have evolved. The result was that in the majority of cases, the manufactured consensus receptor was expressed at better levels than the native human olfactory receptors. "These ancestral receptors have mutated over the years so that they can sense more molecules, but they have also lost effectiveness. This may explain why these ancestral receptors express themselves better than others", adds the researcher.

In addition to unlocking a major problem in olfaction research, this study also enabled Claire de March and her colleagues to identify the human olfactory receptor OR51E2. This receptor, which exists in the human nose, is very well conserved in evolution and is therefore one of the best-expressed native receptors. In 2023, the study of its structure led to the first experimental structure of a human olfactory receptor in history. The researcher and her colleagues achieved this at the University of California (UCSF) using cryo-electron microscopy, which recreates a three-dimensional image from hundreds of thousands of photos of a structure immobilised by cold. This discovery earned Claire de March the Irène Joliot-Curie "Young Female Scientist" Prize for 2023.

The discovery of this structure was also the starting point for a wide range of research and applications. The OR51E2 receptor is expressed not only in the nose but also in the prostate and is suspected of playing a role in cancer cell proliferation and metastasis in prostate cancer. A better understanding of this receptor would therefore have therapeutic implications that go beyond those - already very diverse - of olfaction.

Understanding the impact of respiratory viruses on the sense of smell

Alongside studies on the fundamental structure of the olfactory epithelium - the tissue responsible for odour detection in the nasal cavity - other research teams at Université Paris-Saclay are working to better understand this epithelium's interactions with the external environment. One of these scientists is Nicolas Meunier, a neurobiologist in the Virology and Molecular Immunology Laboratory (VIM - Univ. Paris-Saclay/INRAE).

A specialist in olfaction since 2005, Nicolas Meunier began focusing his research on the interactions between the environment and the nasal cavity in 2015. In 2017, he and his team demonstrated that nasal microbiota - similar to the better-known gut microbiota - influences odour detection. He spent the years that followed studying the interactions of the olfactory mucosa with the immune system. "I am particularly interested in understanding how a respiratory virus can infect the nasal cavity and how the local immune system responds to this infection," he explains. These studies are particularly relevant as they took place a few years before the Covid-19 pandemic, which at the time demonstrated the important role of respiratory viruses in disrupting the sense of smell. "Our team was very reactive when SARS-CoV-2 appeared, because we already had all the tools to understand what was happening," explains the researcher.

Since 2020, Nicolas Meunier, who was then working on the bronchiolitis and influenza virus, has switched his focus to the mechanisms responsible for loss of smell after infection with SARS-CoV-2, one of the most common symptoms of Covid-19. This research led him to propose that the loss of sense of smell observed in a patient with Covid-19 is linked to significant desquamation (destruction) of the olfactory epithelium following viral infection. In 2022, his new study suggested that this destruction of the olfactory epithelium is not directly linked to SARS-CoV-2 infection, but rather to the associated immune response. Neutrophils, the first cells in the immune system to react to infections in the body, are thought to play a major role in destabilising the olfactory epithelium and thus in the loss of the sense of smell.

To achieve these results, the researcher used behavioural studies carried out on different rodents - mice and hamsters - whose olfactory systems are similar to those of humans. However, Nicolas Meunier calls for caution: "The transposition of our results to humans is not straightforward. There are anatomical differences between rodents and humans, and although the hamster model closely mirrors the pathophysiology of mild Covid-19 in humans, there are undoubtedly differences. We can never be certain of anything."

The researcher is now trying to explain the differences between short-term and long-term loss of smell, which he believes are linked to two quite distinct processes. "It is disturbing that some patients are completely anosmic but regain their sense of smell in just a few days. This seems incompatible with the complete destruction of the olfactory epithelium, as regeneration cannot be that quick."

One of the hypotheses put forward by the researcher explains this transient loss of smell by the obstruction of the olfactory cleft, a very narrow passage that allows air to pass from outside the nose to the olfactory epithelium. This obstruction, caused by cell debris resulting from the desquamation of the epithelium by neutrophils, implies a transient loss of sense of smell while the debris is eliminated. If the loss persists, it would be linked to greater destruction of the epithelium following the viral infection. And, depending on the individual, it may take more or less time to regenerate in a context of persistent inflammation.

Further studies are underway to better understand this transient loss of smell - in particular, the difference between several SARS-CoV-2 variants - and to study the mechanisms of virus dissemination via the nasal cavity. An antiviral treatment to limit virus transmission by this route is also being tested on animal models. "There is still a huge amount to study regarding the links between the olfactory epithelium and its environment," adds the researcher. "This is an area that had barely been explored before Covid-19. Many virologists started to look at the nasal cavity and how it works during the pandemic, and there is still a lot of work to be done," he says.

Recreating lost fragrances

Nicolas Meunier is not the only scientist whose field of research has developed more rapidly since the Covid-19 pandemic. This is also the case for Olivier David, a lecturer in organic chemistry at the Lavoisier Institute of Versailles (ILV - Univ. Paris-Saclay/UVSQ/CNRS). While teaching trainee perfumers, cosmeticians and aromaticians, he has noted a renewed interest in the subject since 2020."Covid-19 may not explain everything, but the number of students in these disciplines is growing, and there is a greater social mix," he analyses.

Olivier David joined the Lavoisier Institute in 2005 and specialised in perfumery in 2012. "It all fell into place when I started teaching trainee perfumiers. I discovered that this field had a number of challenges to overcome from a chemistry point of view!" Today, the lecturer devotes a large part of his research to the history of the ingredients used in perfumery. In 2020, he published the chemical and industrial history of polycyclic musks, a family of synthetic molecules widely used in perfumery. "Musk was originally an animal product derived from the secretion of a special gland. But its harvesting results in the death of the animal and is therefore strictly forbidden today. Synthetic musks, which replace the natural molecule, were among the very first discoveries made by chemists in the world of perfumery. I wanted to tell the story of how scientists achieved such feats in the 19th century, and the consequences these discoveries had for industry."

For these studies, performed outside the lab, Olivier David gathered and analysed a large number of archives and publications to reconstruct these little-known parts of history. "The work was made even more difficult as the culture of secrecy is particularly important in perfumery. Some manufacturers did not publish their chemical formulas or discoveries." In 2023, Olivier David also published a history of the great advances in perfumery.

In addition to his work as a science historian, Olivier David is also a chemist; once the history had been unravelled, he set about reproducing certain lost musks using the original methods, to enhance the collections of the Osmothèque, a conservatory of perfumes and perfumery ingredients. As attached to the past as he is to the future, Olivier David is now seeking to reproduce certain molecules with less impact on the environment and health. His latest goal is to reconstitute the scent of birch tar, an odorant used since ancient times but containing substances harmful to the skin, for use in perfumery. "In addition to preserving the heritage of scents and perfumes, I want to provide new, more respectful ingredients for the perfumery of the future," says the lecturer.

A transdisciplinary research subject

In addition to organic chemistry, molecular chemistry and neurology, the sense of smell seems to be a theme that is relevant to many other disciplines. Olivier David, for example, uses his knowledge of the history of chemistry to foster collaboration in literature. "Researcher Érika Wicky specialises in 19th century literature and is interested in descriptions of the smell of painters' studios. She noted that black paints were often cited and therefore concluded that they had a strong and distinctive smell. The idea behind our collaboration is to recreate the smell of painters' studios and better understand the composition of certain paintings," explains the lecturer.

Claire de March also applies her discoveries in fundamental chemistry to more societal applications. In a recent study, carried out with neurobiologist Noam Sobel, the researcher focused on the smell of tears and the consequences of inhaling them. Also in 2023, she succeeded in "resuscitating" the olfactory receptors of a Denisovian and a Neanderthal, two cousins of Homo sapiens who disappeared 30,000 to 40,000 years ago. "The aim was to retrace the evolutionary history of olfactory receptors in the Homo genus, in particular to determine whether the three species had different perceptions of odours," explains the researcher. The results suggest that, while Neanderthals appeared to have a large number of receptors comparable to those of Homo sapiens, most are no longer functional. The olfactory receptors of Denisovans, different from those of Homo sapiens, seemed to function in the same way as modern olfactory receptors. "Our research suggests that Neanderthals had a weaker sense of smell than we do, but that Denisovans were more sensitive to sweet and sulphurous odours." says an enthusiastic Claire de March. "This study is one of the greatest thrills of my career. The receptor we reconstructed had not been active for 30,000 years!"

Linking such research, rooted at the atomic level, with social issues is "very exciting", Claire de March confides. Olivier David confirms: "One of the elements that I find specific to olfaction research is that researchers from very different backgrounds, from biochemistry to philosophy, can exchange ideas and understand each other. Talking about our perception of smells also involves sharing emotions. Few subjects manage to create such links between disciplines," he concludes.

References:

- Billesbølle, C.B., de March, C.A., van der Velden, W.J.C. et al. Structural basis of odorant recognition by a human odorant receptor. Nature 615, 742–749 (2023).

- Olivier R.P. David. A Chemical History of Polycyclic Musks. Chemistry. 2020 Jun 18 ; 26(34):7537-7555.

- Bourgon, C., Albin, A.S., Ando-Grard, O. et al. Neutrophils play a major role in the destruction of the olfactory epithelium during SARS-CoV-2 infection in hamsters. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 79, 616 (2022).

This article was originally published in L'Édition n°25.

Find out more about the journal in digital version here.

For more articles and topics, subscribe to L'Édition and receive future issues: