Citizen science: projects that help advance the sciences thanks to the public

This article was originally published in L'Édition n°25.

Citizen science has become a tool of choice for disseminating scientific knowledge while involving the general public in research work. Citizen science is also making its mark at Université Paris-Saclay, as evidenced by these four citizen projects led or supported by research staff from the university.

Growing beans, hunting for meteorites, watching birds feed, or... collecting stool samples. At first glance, there is no connection between these more or less unusual activities. But they all have one thing in common: they are research projects. Except that in this case, it is not researchers who are carrying out the experiments, but citizens who have volunteered to give scientists a helping hand.

Over the past 20 years, citizen (or participatory) science has become increasingly popular. The number of programmes designed to involve the general public in scientific research continues to grow, in a variety of forms and disciplines. While some projects are just getting off the ground, others are already reaping the rewards of years of citizen collaboration. Some have even been rewarded for their approach, including the INCREASE project, winner of the 2024 EU Prize for Citizen Science last June. To date, over 20,000 volunteers have taken part in this initiative across Europe. A fine performance for the common bean, the focus of this unique initiative.

Decentralising conservation of the common bean

Launched in May 2020, the INCREASE project (Intelligent Collections of Food-Legume Genetic Resources for European Agrofood Systems) "will implement a new approach to conserve, manage and characterise genetic resources, focusing on chickpea, common bean, lentil and lupin," explains Maud Tenaillon, research director at Quantitative Genetics and Evolution laboratory (GQE – Univ. Paris-Saclay/INRAE/CNRS/AgroParisTech) and French relay of the project led by a team from the Università Politecnica delle Marche in Italy. "We believe that legumes have a crucial role to play in the agro-ecological transition. While meat consumption is declining across Europe, there is a real demand for more protein-rich legumes."

While these plants boast significant diversity, the number of varieties cultivated today is much lower than in the past. Fortunately, this diversity is preserved in gene banks, which are responsible for inventorising and characterising the varieties. "The problem is that each gene bank has its own modus operandi, and it is hard to know exactly what is where." This observation was the impetus to launch the INCREASE project: "The idea is to put everything together, to enhance the knowledge and conservation of the four target legumes."

For the common bean, however, the team is taking a novel approach. Rather than leaving the seeds in the hands of professionals in a few places, it has launched a participatory experiment to "decentralise" conservation. "We thought: why shouldn't citizens reappropriate this diversity and play a part in the conservation of genetic resources?" explains Maud Tenaillon. Having started in 2021, the experiment involves asking volunteers to grow beans at home to study the different varieties in different environments.

You don't need to be a plant expert in order to take part in the project. "Anyone can take part, all that is needed is a bit of soil on a balcony, in a garden or a field." After registering, volunteers receive a packet of five seed varieties - plus a control variety - selected from the thousand bean varieties chosen for the experiment. "70% of our varieties come from Europe. 75% are climbers and 25% are dwarfs", explains the researcher from the QGE laboratory. We're basically "demonstrating that a bean doesn't have to be a white bean just a few centimetres long."

Then comes the crucial moment: sowing the beans and starting the observations. Emergence date, leaf shape, pod colour, seed appearance, etc. The plants are scrutinised from top to bottom. "We tried to establish a precise protocol by providing colour scales, measurement grids, etc. To simplify the process, we ask participants to take photos which are then analysed by artificial intelligence, which is capable of automatically measuring the characteristics of leaves, seeds, etc." All the data and photos are sent by the volunteers via the INCREASE CSA mobile app developed for the experiment.

After four campaigns - organised each year from mid-November to the end of February - the team already has thousands of data records. But we'll have to wait and see before these deliver any initial results. "Managing the project, especially sending out the seeds, involves a lot of work", confirms Maud Tenaillon. In 2023 alone, more than 8,000 bags of seeds were sent out by the Italian team. "When the data comes in, it also has to be cleaned, which takes a considerable amount of time." That doesn't stop the researchers from planning to extend the experiment beyond the initially planned five years. Besides scrutinising their beans, the volunteers are now invited to share tips, videos, recipes and even seeds. As long as they follow the instructions provided by the app. "Seeds can't be exchanged any old way!" cautions Maud Tenaillon. That is also one of the objectives of INCREASE: "Make citizens aware that seeds are an important and precious asset."

Eyes to the sky, on the lookout for meteors

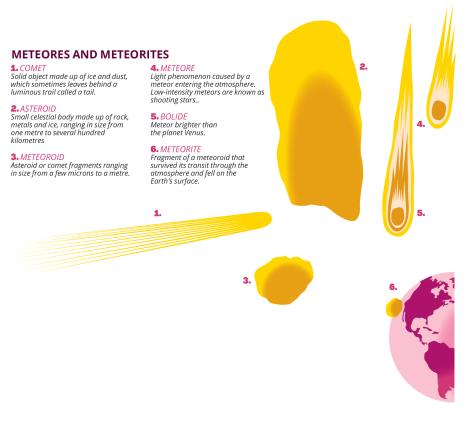

On 26 July, a meteor almost as bright as a full Moon lit up the skies over eastern France. Flying past at 2.00 a.m. and lasting just five seconds, the phenomenon could well have gone unnoticed. But the FRIPON cameras and observers from Vigie-ciel didn't miss it. Thanks to these observations, everything about this meteoroid was already known shortly thereafter: its origin, speed, trajectory, etc. Proof that beans aren't the only things to benefit from citizen science. The FRIPON and Vigie-ciel, programmes, run by the National Museum of Natural History (MNHN), the Observatoire de Paris and Université Paris-Saclay, are another example.

FRIPON (Fireball Recovery and Inter Planetary Observation Network) was set up in 2014, following two events a few years earlier: a meteorite that fell in the town of Draveil (Essonne) and a large shooting star that flew over Brittany. "At the time, we received a lot of eye-witness reports, but we couldn't respond to anyone," recalls Sylvain Bouley, a planetologist attached to the Géosciences Paris-Saclay laboratory (GEOPS – Univ. Paris-Saclay/CNRS). "Having sensed the interest, we decided to set up a network of cameras capable of monitoring the sky 24 hours a day and detecting meteorite falls."

To make sure the human witnesses who are willing to share their observations were not overlooked, a second programme, Vigie-ciel, is taking shape. "That is the participatory aspect of FRIPON," explains the lecturer and co-founder of both programmes. "Vigie-Ciel offers witnesses the possibility to fill in a form to tell us what they saw." This is done through a dozen questions developed in partnership with the American Meteor Society. "These reports quickly give us an idea of the intensity of the event: when you have two hundred eye-witness reports, you know that something important has happened. It is an early warning to go and look at the camera data".

The performance of FRIPON and Vigie-ciel testifies to their effectiveness. Since 2018, the two hundred cameras, installed in laboratories, planetariums and amateur observatories in France and other countries, have spotted over 10,000 bolides - large shooting stars. As for Vigie-ciel, it has notched up almost 13,000 reports for around 4,000 observed events. This latest programme doesn't just encourage volunteers to scan the skies. It also takes them on meteorite hunts. "This is the second aspect of Vigie-ciel: we have regional coordinators who provide training and organise meteorite hunts when meteorite falls are suspected," confirms Sylvain Bouley. "Since 2018, there have always been one or two falls a year for which we have organised hunts. But we soon realised that looking for meteorites in France isn't easy." The first successes of the project only came in 2023.

In February of that year, an asteroid was spotted seven hours before it was timed to enter the atmosphere. Once the alert was given, the FRIPON network and the Vigie-ciel community were mobilised. "The next day, we knew that something had fallen in Normandy. The day after that, we were out in the field and the meteorite had been found within two days", recalls the planetologist. "It is the nicest example of citizen science, because it wouldn't have been possible without all the amateurs who filmed the entry of the asteroid, and without all the local residents who came to look for the meteorite with us. The asteroid was found in a field by an 18-year-old student. We could have totally missed it."

The second success came in September after another bolide was spotted in the sky. Astronomers suspected there would be a fall in Sologne, but in private forests, which were difficult to access for a hunt. And then came a surprise: a resident contacted a relay from FRIPON/Vigie-ciel. The object had landed on her property, destroying her garden table. "The surveillance camera even recorded the sound of the asteroid falling on the table! It is another great story of participatory science, because it meant we could inform this local resident about the event and acquire the meteorite."

Will stool donations soon shed light on the secrets of the microbiota?

The health sector is no exception to the boom in participatory research. While some citizens are keeping an eye on cosmic rocks, others are opening up an unprecedented window to scientists onto the billions of micro-organisms that inhabit our gut. Le French Gut is the name of the initiative launched by the MetaGenoPolis unit (MGP – Univ. Paris-Saclay/INRAE), in collaboration with Greater Paris University Hospitals (AP-HP), to accelerate research into gut microbiota. The aim is, by 2027, to recruit no fewer than 100,000 volunteers who are willing to donate a stool sample. "We're looking for individuals of any age, anywhere in France, in good health or otherwise," explains Anne-Sophie Alvarez, communications manager for the project.

Le French Gut is part of a large-scale international initiative, the "Million Microbiome of Humans Project" (MMHP), which aims to build the world's largest database of human microbiota, with a million samples from the gut, skin and mouth. "I have been working on gut microbiota for 40 years and have seen the field evolve considerably," enthuses Joël Doré, Scientific Director of MetaGenoPolis and Le French Gut project, and a researcher at the Micalis Institute (Univ. Paris-Saclay/INRAE/AgroParisTech). "We have gone from studies on a few dozen subjects to studies on a few hundred and then a few thousand individuals. But it is obvious that this is not enough. We really need a very large number of people, in order to characterise the microbiota of the human population and identify its specificities in health or disease."

Characterise the microbiota, i.e. better understand its composition. This is one of the initiative's research orientations. We now know that the composition of the intestinal microbiota varies significantly from one individual to another. Research has also made it possible to establish links between the microbiota and certain chronic diseases such as diabetes, obesity, cancer and inflammatory bowel disease. But what actually is a healthy microbiota? "We want to build up a reference of microbiota for the French population, related to both healthy and sick individuals," explains the researcher. "We also hope to better understand how dietary habits, lifestyles and exposure to certain environmental factors can influence the microbiota. Finally, we want to take our research into the links between the microbiota and the most common chronic diseases a step further."

Following a pilot phase launched in 2022, Le French Gut is shifting up a gear, with a target of 100,000 donations. To join the cohort, volunteers have to register online on the project's website and fill in a 20-minute questionnaire on their state of health, diet and so on. "This data is crucial, because it will be cross-referenced with the respondents' microbiota," explains Anne-Sophie Alvarez. A kit is then sent to their home to collect stool samples, which are then returned by post. "It is a simple swab, we don't really need much."

All the samples are then verified and anonymised before being sent to MetaGenoPolis for analysis. From the samples, "we extract and sequence the DNA to determine the microbial genomes present," explains Joël Doré. "We have worked intensively on the logistics for collecting the samples, because the target of 100,000 is crucial." The prospects of the project are just as important. "The biggest potential imaginable is predicting diseases. Thanks to the health data to which we have access, we will be able to track individuals for at least 20 years. If some of them develop diseases, we can go back to the samples and try to identify predictive signatures in the microbiota."

Collecting a stool sample can be a daunting experience. And yet, Le French Gut had no problems recruiting the 3,000 volunteers for the pilot phase, who were brought together in just one week. "We were slightly surprised by the public's response," admits Joël Doré. But "the general public is increasingly aware of the microbiota issue," assures Anne-Sophie Alvarez. The samples from this pilot phase are currently being analysed.

A serious game to mimic birds at feeders

Playing games to advance research. This other form of citizen science is proving its worth with the BirdLab project, launched in 2014 by Carmen Bessa-Gomes and François Chiron, lecturers at the Ecology, Systematics and Evolution laboratory (ESE – Univ. Paris-Saclay/CNRS/AgroParisTech), in collaboration with Vigie-nature and the National Museum of Natural History (MNHN). With this initiative, citizens are invited to witness the behaviour of birds at feeders in winter through a serious game which is available on the BirdLab mobile app.

You don't need to be an expert in ornithology to take part, or even be familiar with the 29 species featured in the game, selected from among the most common species. Volunteers simply stand in front of two identical feeders in a garden, balcony or public place, which is filled with seeds or fat balls, and watch the birds land on them. Once the game is launched, "each game lasts five minutes, during which players replicate the movements of the birds in real time, selecting the species that are there and moving them to the feeders," explains François Chiron.

It is a fun activity for the volunteers, but above all extremely instructive for the ecologists. "The aim is to study the recruitment dynamics of species at feeders and the interactions between them." Are some species avoided by others because they are more competitive? On the other hand, do some of them facilitate the arrival of other bird species that are more followers or even pilferers? And are these same behaviours observable between individuals of the same species? These are the questions the BirdLab team intends to answer using the data it has collected. “We are also trying to understand how these clustering or avoidance behaviours vary according to the environment, weather conditions, landscape, etc." adds François Chiron.

During the observation campaigns, which take place every year from mid-November to mid-March, each participant plays as many games as they wish. Ten years after the game was launched, there have been almost 100,000 games, and millions of interactions observed between the birds. Thanks to this project, "we have obtained much more data than with a conventional study based on scientists' observations." But the participative aspect doesn't stop there. "In ecology, the questions we ask are based on observations. That's why it is crucial that we develop the experiment in line with the actual observations and questions of the players," notes François Chiron.

This is how, for example, the ring-necked parakeet became a BirdLab species. "People were worried about its presence at feeders, particularly in the Paris region, and wondered whether they should be prevented from feeding there." This surveying and the data collected with the game led to initial results on the subject in 2020. The verdict: although perceived as invasive, the parakeet is no more competitive at the feeder than other species of a similar size, such as the collared dove or the magpie. While these results may challenge the conventional wisdom, the data generated by BirdLab confirm certain behavioural traits already well known in other birds, such as the solitary nature of the robin or the aggressive tendencies of the blue tit.

Whether it is beans, meteors or birds, keeping these projects going over the long term is no easy task, especially when they involve tools such as mobile apps or cameras that require technical maintenance. "That was the main difficulty we encountered," admits François Chiron. On top of that, there is the need to keep the programmes interesting to recruit new volunteers for each campaign. For the ecologist François Chiron, the stakes of these projects go beyond gathering data: "What I find great is the impact of our work on nature conservation. With citizen science, people observe, learn and develop a certain empathy for birds. Various studies have shown that observing nature also has benefits for individuals' health and well-being. I think we underestimate the indirect positive effects of this kind of work."

References :

- INCREASE : www.pulsesincrease.eu/experiment

- Vigie-ciel/FRIPON : www.vigie-ciel.org

- Le French Gut : https://lefrenchgut.fr/

- BirdLab : www.birdlab.fr

This article was originally published in L'Édition n°25.

Find out more about the journal in digital version here.

For more articles and topics, subscribe to L'Édition and receive future issues: