Artworks, cultural goods: Re-examining questions of provenance and restitution

This article was originally published in L'Édition n°26.

Whether it's artworks or cultural goods looted during wars or colonisation, questions of provenance and potential restitution regularly resurface. What is the current situation regarding the laws on cultural goods? What legal questions do these topics raise? Recent work conducted by researchers at Université Paris-Saclay provides some answers.

Inalienable, imprescriptible and unseizable. These are the principles which applied to the 80 million or so objects in the French public collections in 2024. These cultural goods, with their diverse origins and histories, are nevertheless difficult to define and above all to trace on the international scene. Marie Cornu, director of research and jurist at the Institute of Social Sciences in Politics (ISP - Univ. Paris-Saclay/CNRS) sums up the main characteristics: "A cultural good is a good with a recognised symbolic value. French law provides for special legal regimes for these goods, rendering them unavailable - they are said to be 'off the market' - with the aim of preserving and bequeathing them."

In 2012, Marie Cornu published a Dictionnaire comparé du droit du patrimoine culturel (Comparative dictionary of cultural heritage law) together with Catherine Wallaert and Jérôme Fromageau, in which she compared the main concepts and terminology of cultural heritage law in six European countries. The aim was to document the different sensitivities between States, in order to identify potential difficulties of interpretation in both domestic and international law. A new edition of the dictionary, planned for April 2025, will include four new countries.

In her most recent book, Entre-temps: le bien culturel et le droit (In the meantime: cultural property and the law), published in 2023, Marie Cornu focuses in particular on the ”timeless” principles of inalienability and imprescriptibility. In law, prescription means no longer having any effect on a good after a certain period of time. In the jurist's view, the principles of inalienability and imprescriptibility are "two very powerful forces which, in a sense, mean that these goods transcend time and the law". The measures imposed for these objects cannot expire by the passage of time.

While these fundamental principles, enshrined in the French Heritage Code, are primarily intended to conserve public cultural goods, they also spill over into major political issues. As the jurist explains, "even if the rule of inalienability of cultural goods does not have any constitutional value - it can be derogated from in special laws - it is likely to thwart requests for restitution in the international arena". These derogations pose a problem when a state that was previously a colonial empire has objects in its collections that were taken or displaced during this period. In effect, when international claims are made on these goods, any restitution is refused because, under the law, it is not possible to remove them from the collections.

Case-by-case restitution

How can we overcome this legal hurdle and restitute cultural goods to their countries of origin? In her book, Marie Cornu explores some of the legal mechanisms already used to circumvent the rule of inalienability. Among other things, she highlights the Korean Archives affair, nearly 300 royal manuscripts seized by the French Army in 1866 and the subject of demands for restitution in the 1960s. "This request was initially refused due to the principle of inalienability, but in view of the inestimable importance of these archives for the country and the intimate link with its history, a renewable temporary loan agreement was concluded with Korea. Today, although the loan has expired, the States in question are well aware that Korea will never return its archives and that France will not demand their return." However, as the jurist explains, the growing power of such claims is becoming an international political issue that needs to be taken seriously. In her view, "refusing requests for restitution based on the principle of inalienability is no longer sufficient" and "this type of alternative method, which tweaks the loan or deposit mechanisms of French law to use them for purposes other than those for which they were designed, is hardly satisfactory". A new approach for restitutions is overdue.

A turning point came in 1970 when UNESCO adopted a convention on the prevention of the illicit import, export and transfer and the return of cultural goods, which, among other things, legitimised requests for restitution. It therefore lays down rules for the return and restitution of cultural goods within the international legal order. Three years later, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution on the "prompt and free" restitution of artworks to countries that fell victim to expropriation. The claimant states quickly relied on these texts to justify their demands for the restitution of goods seized during the colonial period. The problem was that, like any other international treaty, the 1970 Convention only came into force once it had been ratified by the States, i.e. 1997 in the case of France.

As underlined by Vincent Négri, a jurist and researcher at the Institute of Social Sciences in Politics (ISP - Univ. Paris-Saclay/CNRS) and specialist in the restitution of seized goods, "none of the adopted conventions can reach the acts of dispossession of populations during the colonial period that stretches back in time." Moreover, colonisation was considered a "sacred mission of civilization" by Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations in 1919, and this assessment still seems to be more or less part of contemporary debates. Beyond these political considerations on the link with the colonial period, no text of international law has come to overturn the values put forward by article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations.

There are only a few exceptions today, and they involve specific cultural goods such as human remains. On a different level, regarding the crimes against humanity committed by the Nazis, the law governs the restitution of property stolen from Jewish families between 1933 and 1945. For this property, specific laws were adopted in 2023 to waive the principle of inalienability or downgrade objects in French public collections in order to make it possible to restitute them. However, a general law covering all artworks seized during the colonial period appears to be more difficult to implement. An initial draft law, submitted to the French Council of State for its opinion, has been rejected for the time being. According to Vincent Négri, who is following the case closely, the Council of State did not reject on principle the introduction of a mechanism to govern the restitution of goods from the colonial territories and then appropriated by mainland France. The idea of implementing a general law is "simply postponed, not dead and buried".

For Marie Cornu, certain fundamental issues still need to be discussed: "There is still no consensus on the scope to be taken into account for this law. Do we need to set limits in terms of geography (Africa) or time (the colonial period)?" Pending the adoption of a general law, specific texts are still voted on a case-by-case basis to respond favourably to requests for restitutions submitted to France. In 2024, a draft law addressed the restitution of human remains to overseas territories, as the law on human remains adopted in 2023 only applies to requests from foreign countries and not to overseas communities.

A new relational ethics

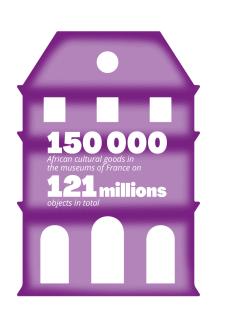

In November 2017, French President Emmanuel Macron expressed the wish, in a now-famous speech at the University of Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso), that "within five years, the conditions will exist for temporary or definitive returns of African heritage to Africa". In 2024, art historian Claire Bosc-Tiessé estimated that there were around 150,000 items of African cultural goods in French museums, out of a total of 121 million objects. Emmanuel Macron commissioned two academics, the Senegalese writer Felwine Sarr and the French art historian Bénédicte Savoy, to produce a report on the situation. Vincent Négri, an expert in African heritage law, was responsible for the legal aspect of the report. "This speech marked a major break with European states, which up until then had always refused to respond favourably to requests for restitution from states that had former colonies. The report proposes a methodology for restitution designed to restore a form of equity and increase the presence of African heritage on the African continent."

Submitted to Emmanuel Macron on 23 November 2018, the report recommends, among other things, amending the Heritage Code to include a section on "the restitution of cultural goods on the basis of a bilateral cultural cooperation agreement with former colonial countries". This new section would simplify and speed up the restitution process, as restitutions could be made without recourse to a special law, and without betraying the principle of the inalienability of French collections. Following the report, 26 objects from the treasures of the ancient kingdom of Abomey were returned to Benin, and just one, a historic sword, was returned to Senegal in October 2021, again thanks to a specific law.

Beyond its legal expertise, the text also calls for a rethink of relational ethics between African and European countries. An important question for Vincent Négri, who is particularly interested in the impact of restitutions on the countries of origin and the various forms restitutions can take, beyond the journey of the object. "When the Sarr-Savoy report was being drafted, we held a workshop in Dakar with museum directors from various African countries to reflect together on questions of restitution. When asked what they intended to offer in exchange for the returned objects, the responses were very interesting. While the knee-jerk reaction was that nothing would be given to fill the empty space in European museums, some then suggested exchanging the returned goods with contemporary art, for instance."

These new dynamics of cultural exchange between the African and European continents add to the questions of provenance raised by the objects seized during the colonial period. Today, only a state can return cultural goods to another state, but certain cultural goods are the property of populations or communities within states that did not exist during the colonial period. An aspect that was "overlooked", according to Vincent Négri, who also works on these links between state and communities on the African continent. For him, beyond the material aspect of restitutions, "the important thing is to reflect on what these restitutions generate from a social, political and cultural perspective".

In his drive to give a voice to the people in question and to "pass on the baton", Vincent Négri recently launched a project with UNESCO for a collective work on African heritage rights. Planned for autumn 2025, the project will showcase the work of "a young generation of researchers in Africa" who are writing on questions such as restitutions and interdependencies between countries in the area of heritage.

In search of authenticity

While the question of provenance is crucial in restitution cases, it is equally important in the art market. Françoise Labarthe, professor of Private Law at Université Paris-Saclay and member of the Board of Directors of the Centre for Study and Research in Intangible Asset Law (CERDI - Univ. Paris-Saclay), is a specialist in this matter. Co-author with Tristan Azzi of Le droit du marché de l'art (Art Market Law) published in 2024, she has taken part in various conferences on the themes of traceability, provenance and authenticity.

In law, the concept of "provenance" has two aspects: it refers either to the place from where the good originates (the country of origin), or to the journey of the object as a whole. For Françoise Labarthe, being familiar with the good's journey from genesis to exhibition reinforces its authenticity. As she writes in her article Dire l'authenticité d'une œuvre d'art (Declaring the authenticity of a work of art) published in 2014, this authenticity - which occurs, for example, by the existence of a certificate of authenticity or archives - "makes or breaks a work's reputation" and "sets its value". More importantly, "provenance attests to the lawful origin of the work, and therefore grants the buyer the peaceful enjoyment of their property".

In Françoise Labarthe's view, the question of the lawfulness of works is becoming increasingly important in the art market, and "the demands are becoming more and more intense in this area". Since 1981, a decree has obliged sellers, if requested by the buyer, to "issue an invoice, receipt, sales note or extract from the minutes of the public sale containing the specifications they have provided as to the nature, composition, origin and age of the object sold". On the other hand, in April 2019, a regulation of the European Parliament restricted imports of cultural goods into the European Union by requiring certificates of lawful export from their state of origin.

While these new measures are designed to combat the sale of looted cultural goods and protect buyers, they also have a counterproductive effect. "The art market is shrinking because selling archaeological goods is becoming very difficult," notes Françoise Labarthe. "Many objects bought in the 20th century were sold without an invoice, or came from an inheritance. These objects without provenance are now unsellable on the market. And it is all the more injurious that non-EU member states not subject to these regulations remain free." Some of these "orphan" objects without provenance become, in turn, vectors for online trafficking, or, in some cases, manage to circumvent the regulations with false certificates.

In 2024, Françoise Labarthe set up a working group with art market professionals such as the Office central de lutte contre le trafic des biens culturels (Central Office for the Fight against Trafficking in Cultural Goods - OCBC). Their remit is to provide art dealers and buyers alike with an instruction manual to help them meet the requirements of the law and the needs of professionals. A reference document of this kind would assure all stakeholders of the legality of the goods on the market. However, as Françoise Labarthe points out, the requirements vary from one domain to another and from one profession to another. Drawing up a list of recommendations that can be adapted to the wide range of cases, like a general law on the restitution of artworks, is therefore no straightforward task.

The new profession of provenance researcher

As is the case for artworks, provenance research for cultural goods is growing in importance, both to certify the value of a work and sell it on the market, and to identify and prove potential illegal exports, which sometimes leads to their restitution. A new speciality has emerged in recent years to meet these various challenges: provenance research training is emerging within art history or heritage law courses. Leading institutions such as the Musée du Quai Branly - Jacques Chirac and the Musée du Louvre already have such experts among their staff.

For Marie Cornu, a long-time lecturer in heritage law, this new profession of provenance researcher is first and foremost that of an investigator. "It's an interdisciplinary job. You have to cross-reference the various sources, piece together a jigsaw puzzle by looking at what is written, or not, in the archives. The aim is to determine how lawful the provenance is, to understand the journey and history behind each work." However, as the jurist points out, "provenance research does not mean restitution. The objective of museums that have provenance departments is to provide guidance on their works and put them in context. It often involves more historical expertise than legal".

As regards the art market, although illicit trafficking remains a major problem, Françoise Labarthe remains confident: "Young auctioneers are much more aware of these issues than other generations. They can easily spot the first signs of looted artworks." The only drawback is that provenance researchers, who are still few and far between, "are mainly interested in exceptional works, which are often the subject of disputes. It is still difficult to have the same requirements for all the objects sold on the market".

In January 2025, an intensive week of workshops and conferences for PhD and Master’s degrees’ students at Université Paris-Saclay was devoted to heritage which is the subject of disputes. Marie Cornu, who also organises seminars on the theme of heritage at Université Paris-Saclay, sees this as an excellent way for these students to discover the numerous issues surrounding heritage questions. "Heritage has become a veritable subject at Université Paris-Saclay," she enthuses. "It is no longer regarded as a theme, but as a research subject of interest to many disciplines, in the humanities and social sciences as well as in the experimental sciences," she concludes.

References :

- M. Cornu, Entre-temps : Le bien culturel et le droit, Dalloz, 2023.

- F. Sarr, B. Savoy, Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain. Vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle, 2018

- T. Azzi, F. Labarthe, Le droit du marché de l’art, LGDJ, 2024

- V. Négri, « Restituer, partager, réparer : penser la légalité de demain », Cahiers d’études africaines, n° 251-252, 2023, pp. 527-541.

Cover photo : Presentation of the artworks of Abomey on the collections platform of the musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac from 2012 to 2021, photo shot in 2018.

© musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, photo Léo Delafontaine

This article was originally published in L'Édition n°26.

Find out more about the journal in digital version here.

For more articles and topics, subscribe to L'Édition and receive future issues: