Menopause: demystifying a taboo for women's health

This article was originally published in L'Édition n°26.

Menopause is a natural stage in a woman's life, and its effects are felt both in terms of health and quality of life. But it is still a taboo subject. At Université Paris-Saclay, researchers are working to gain more insight into this important physiological stage and its manifestations, in order to improve care and remove the taboo surrounding it.

By 2030, around 1.2 billion women will be aged 50 and over, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). All of these women will be affected by menopause, the stage at which their reproductive function comes to an end. With an average life expectancy of 85 years for women, this means that many will live more than a third of their lives in menopause. In spite of that fact, this physiological process remains a largely taboo subject. "Women know very little about menopause, even though it's one of the stages in the continuum of their lives," stresses Micheline Misrahi-Abadou, professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the Faculty of Medicine Paris-Saclay.

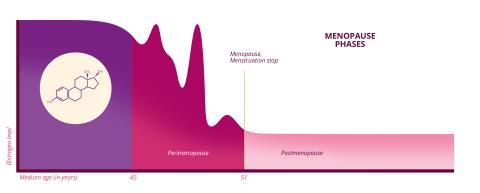

Menopause is characterised by the cessation of ovarian function, and is marked by the end of monthly menstruation for a consecutive period of at least one year. However, the phenomenon is highly variable: it can occur as early as 45 years old and as late as 55 or even later, with an average age of 51 in France. "Before the age of 45, we refer to early menopause, and before the age of 40, premature ovarian insufficiency, which corresponds to pathological infertility," explains the researcher who heads the Molecular Genetics of Metabolic and Reproductive Diseases Unit (UGM3R - Univ. Paris-Saclay/AP-HP) at Bicêtre Hospital. But this cessation of ovarian function does not suddenly occur. On the contrary, it is a lengthy process that lasts several years. The transition period leading up to the menopause is known as the perimenopause (called pre-menopause in French).

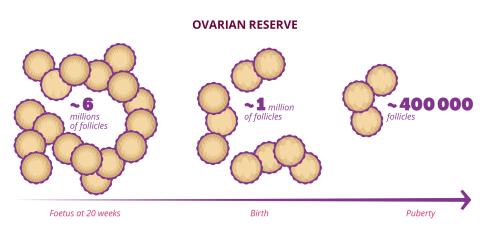

The duration of women's reproductive years depends on their ovarian reserve, the stock of follicles contained in the ovaries. "These follicles are small spheres that contain the oocytes as well as protective and nutritive cells," explains Micheline Misrahi-Abadou. This stock of follicles is only formed once in a woman's life, during prenatal development. By the seventh month of pregnancy, the female foetus has an estimated seven million follicles. At birth, only one million remain, then 400,000 at puberty. And this stock diminishes steadily throughout the woman's reproductive years. "A woman will ovulate only about 500 times during her reproductive years. The main cause of reduced ovarian reserve is therefore not ovulation, but a mechanism of follicular atresia, i.e. spontaneous destruction of follicles."

Can genetics help predict the menopause?

Although atresia has been identified, its mechanisms are poorly understood. As such, it is impossible to predict when menopause will occur. "There are currently no assays or biomarkers to predict when the ovarian reserve will disappear," confirms Micheline Misrahi-Abadou. However, genetics has recently opened up a new avenue. "We know very little about the genes that control human fertility. But we do know that the age of menopause is controlled to a significant extent by genes. There is up to 85% correlation between a woman's age at menopause and that of her mother." Similarly, "we know that women are five times more likely on average to have an early menopause or premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) if there is already a case in their family."

In a study published in 2022, Micheline Misrahi-Abadou and her team focused on patients with POI. Genetic causes were identified in 30% of the cases. What is more, scientists have identified around a hundred genes which, when they carry significant abnormalities, lead to POI or early menopause. "Interestingly, we see that these are the same genes that control the age of physiological menopause. Depending on the woman, they will function more or less effectively, and therefore lead to an earlier or later menopause." Even more interestingly, the genes most often involved belong to a family known to play a major role in DNA repair.

For the specialist, this comes as no surprise: "You have to imagine that the oocyte formed before birth lives for 50 years on average, without dividing or repairing itself. And all that time, it is subjected to various assaults, by internal or external toxins, which in particular alter its precious DNA." Repairing this DNA would therefore foster the survival of oocytes. Similarly, the team identified other gene families, one of which is involved in the growth of follicles and the other in metabolic and mitochondrial functions. "Mitochondria provide energy to facilitate follicular growth and maturation of the oocyte. Without energy and with metabolic alterations, it can no longer function," underscores the researcher, whose UGM3R laboratory has been designated a French national reference laboratory for genetic infertility.

These discoveries have prompted changes in European recommendations for the care of patients suffering from premature ovarian insufficiency. But Micheline Misrahi-Abadou believes that the ramifications go much further. Ultimately, this research could lead to a genetic test which could assess the quantity and quality of ovarian reserve, and therefore predict the menopausal age of every woman. With such a test, "women would be able to organise their reproductive and professional lives, because having your menopause at 47 or 55 years old is not the same thing, given that fertility drops significantly in the ten preceding years."

Hormonal variations that play havoc with the body

In biological terms, the phenomenon is not simply a question of the end of the ovarian reserve. It is also characterised by significant hormonal variations. During perimenopause, "there is a drop in the main female hormone, oestrogen, as well as progesterone," explains Marianne Canonico, a researcher with the Exposome, Heredity, Cancer and Health team at the Centre for Research in Epidemiology and Public Health (CESP – Univ. Paris-Saclay/Inserm/UVSQ). "But this drop is not continuous; it is a period of imbalance. In reality, we observe peaks, with periods of hyperestrogenism [excessive oestrogen production] and hypoestrogenism [insufficient oestrogen production]".

These hormonal changes are responsible for the disruptions to the menstrual cycle observed during perimenopause. They are also responsible for so-called climacteric symptoms: hot flushes, night sweats, disrupted sleep and genitourinary problems. While the origin of these symptoms is not fully understood, we do know that oestrogen affects various systems in the body, including the brain, cardiovascular system, muscles, bones, mucous membranes, etc. As these hormones decrease, so do their effects on the body.

However, the manifestations of menopause, and their intensity, are highly variable. According to the French National Institute for Health and Medical Research (INSERM), 20-25% of women affected show moderate to severe symptoms that affect their quality of life. Hot flushes and sleeping problems top the list of the most debilitating complaints. But mental health can also come under strain. "Pre-menopause is a vulnerability window for depression," emphasises Hugo Bottemanne, psychiatrist and researcher with the MOODS (Depression, Suicide, Medication) team at CESP. "It is estimated that, during this period, 30% of women experience depressive symptoms such as lack of energy and pleasure, and irritability."

The psychological problems sometimes precede the climacteric problems. They can also exacerbate them. "Depressed women wake up more often during the night, and have hot flushes. Conversely, troubles sleeping linked to climacteric symptoms increase the risk of depression." Here again, the mechanisms involved still need to be studied. "We see an intriguing double correlation between climacteric symptoms and depressive symptoms: antidepressant treatments reduce the former, while treatments for climacteric problems improve the latter," explains the researcher. Do these problems share common pathological pathways in the body? That is not known, but hormonal variations could well serve as a common base.

Depression is twice as common in women as in men. And oestrogen has a lot to do with that. "These hormones have an effect on both brain activity and morphology, for example by modifying the conformation of neuronal networks and the way they interact with each other. They also influence some neurotransmitters," explains the psychiatrist and co-author of the book La dépression au féminin (Female depression). Periods of major hormonal change are therefore vulnerability windows for women. "Premenopausal depression, like postpartum depression after pregnancy, is linked to a period of life changes associated with stressors that combine with hormonal changes, like a snowball effect."

To gain insight into the causes of female depression, Hugo Bottemanne explores the hypothesis of interoception. In order to interpret the world around it, the brain relies on perceptions of the external world. This is called exteroception. But the brain also processes all the physiological signals coming from the body. This is called interoception. "Emotional sensitivity varies according to how these signals are processed. We see that with psychiatric problems, there is a dysregulation of these processes. The brain does not perceive signals, process them, or regulate them very well." The hypothesis is that over the course of their lives, and in particular at certain periods such as pregnancy and menopause, women undergo significant interoceptive changes that can disrupt the brain's processing of signals and increase the risk of depression.

A negative cultural perception of menopause

But the researcher believes that this hypothesis is inadequate in explaining the excessive prevalence of depression in women. It is also thought to be brought on by social factors, in particular during the menopause. "The cultural perception of menopause is one of the stressors. In the West, we have many stereotypes on this subject that are not found in other cultures," observes the psychiatrist. The word "menopause", for example, has no equivalent in Japanese. In Japan, ageing is called by a term that applies to both men and women, and includes everything from the end of menstruation to hair turning white.

"In our society, menopause is still perceived as demeaning and unfair for women compared to men, who remain fertile for a long time. On the contrary, it's not at all unfair: women have two lives, a reproductive one and an economic and social one," asserts Micheline Misrahi-Abadou. As she explains in her recent book, Nouvelles fertilités, nouvelles familles, nouvelle humanité (New fertility, new families, new humanity), it's no coincidence that menopause, almost unique in the animal kingdom, has emerged in humans. "There must necessarily be a reason for menopause because, from an evolutionary point of view, it makes no sense for an individual to survive who is unable to reproduce".

Various hypotheses have been put forward to explain this evolutionary oddity. One of them highlights the risks to women's lives associated with pregnancy and childbirth. With the enlargement of the cranium and modification of the pelvis that occurred in the Homo genus, childbirth complications became more frequent, with risks for both mother and child. Combined with the risk of chromosomal abnormalities, which increase the older the mother is, this argument would favour limiting the reproductive years so as not to jeopardize the survival of women and children.

Among the theories put forward, another suggests that by relieving women of their reproductive function, menopause gives them a more important role in social and economic life: "In hunter-gatherer societies, it has been observed that menopausal women are more economically productive. They are the ones who acquire the most skills and knowledge, passing them on to the next generation." This same pattern can be found in the few other species that go through menopause, such as killer whales, whose pods are generally led by an older female.

A treatment called into question in the 2000s

While menopause is bearable for many women, the associated problems can turn it into a real ordeal for some. To mitigate the symptoms, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is offered, which compensates for the drop in hormone levels by adding oestrogen, with or without progesterone. "Before the 2000s, over 50% of menopausal women were treated. But today, less than 10% are," explains Marianne Canonico. This drastic fall comes in the wake of "huge disruption following the publication of two American trials in 2002 and 2004".

Carried out on around 26,000 post-menopausal subjects, these trials highlighted increased risks of breast cancer and various cardiovascular pathologies in women on HRT. "That completely called into question the risk-to-reward ratio of the treatment," continues the researcher. But the treatments given in the United States differ to a significant extent to those in France. "The Americans use what we call conjugated equine oestrogens. These molecules are sourced from pregnant mares, and bear no resemblance whatsoever to the molecule used in France, 17-beta-estradiol, which is identical to the circulating biological molecule," ensures Marianne Canonico. They also use a synthetic progesterone, very different from the bioidentical molecule, micronised progesterone, used in France.

The method of administering this treatment is also different, being mostly given transdermally (patch or gel) in France and orally in the United States. "The transdermal route represents a fundamental difference. When a drug is swallowed, it passes through the liver, where it triggers the coagulation cascade. Administered transdermally, the molecule only passes through the liver later on, after having been partially degraded. This effect is therefore avoided." In 2007, Marianne Canonico took part in a study on French treatments and their impact on the risk of thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The findings of the American trials were not repeated, even when women with existing risk factors for venous thromboembolism were included.

"Although these results have since been confirmed by other studies, they should be treated with caution as they are based on observational studies," cautions the researcher. But they tend to reassure patients about the risk-to-reward ratio of HRT, at a time when the recommendations have been considerably refocused. Going forward, the treatment will only be indicated in the case of problems that affect quality of life, taking into account the individual risks of each patient. The indications are to "give them the minimum dose for the shortest duration" so they are exposed as little as possible to the potential adverse effects.

Understanding the long-term effects of menopause

But what happens after the menopause? What long-term effects does lower oestrogen have on the body? These are the questions explored by Marianne Canonico and her team at CESP. "Today, a woman is exposed to this menopausal period for one third of her life. It is therefore important to understand the effects on women's health, ageing, cardiovascular health, neurodegenerative diseases, cancers, etc."

For their studies, the researcher and her colleagues focus on the overall hormonal exposure of women. In other words, from the age of menarche (first menstrual cycle) to natural or artificial menopause (in the case of surgery or cancer, for example), taking into account the number of pregnancies and children, the use of contraception and any treatment for fertility or menopause. The aim is then to explore the effect of these characteristics on the relevant parameters. For example, a study published from 2023 focused on the walking speed of 34,000 women aged 45 and over from the French Constances cohort. Besides being easy to measure, walking speed is "an integrative parameter that is highly predictive of a person's health during ageing, with good walking ability being associated with a lower risk of falls, hospitalisations and death," explains Marianne Canonico.

Their work points to a lower speed in women who have gone through menopause before the age of 45, compared with women who have gone through menopause between the ages of 45 and 55. Moreover, this parameter appears to be significantly lower in subjects who had fewer reproductive years (between menarche and menopause). "These results are consistent with our initial hypothesis, that oestrogen has a beneficial effect on walking speed," summarizes the researcher, underlining the cardioprotective and neuroprotective roles of the hormones, as well as their positive influence on inhibiting bone resorption and muscle mass.

In a more recent study, the team used data from the E3N cohort, including almost 100,000 French women monitored since 1990, focusing this time on Parkinson's disease. "Our original hypothesis was that women exposed to oestrogen for the longest time or at the highest levels would not develop the pathology to the same extent. We obtained results that are not always easy to interpret, but that seem consistent with the neuroprotective effect of these hormones." The results indicate that early or late menarche, whether a woman has had several children or an artificial menopause, especially at an early age, are factors associated with Parkinson's disease.

"It is important to stress that we can't draw any causal conclusions from our research," cautions Marianne Canonico. "That is the principle of observational epidemiology. The idea is to take into account different parameters and find out whether or not they are associated with a risk of becoming ill several years later. We can then adopt a more targeted prevention strategy." Gaining more insight into the effects of menopause, in order to provide better care and prevent associated pathologies, that's what this research is all about, given that the subject remains underexplored, according to Micheline Misrahi-Abadou.

"Our poor understanding of menopause has a significant cost on women's health. By not treating the symptoms that need to be treated, we create pathologies that take a far heavier toll on society, such as cardiovascular disease, which is the leading cause of death for women," reiterates the specialist. "That shows the need to better inform the general public, but also the medical profession to treat the women who need it."

References :

- M. Misrahi-Abadou et B. Cyrulnik, Nouvelles fertilités, nouvelles familles, nouvelle humanité, Odile Jacob, 2024.

- Heddar et al. Genetic landscape of a large cohort of Primary Ovarian Insufficiency: New genes and pathways and implications for personalized medicine, EBioMedicine, 2022.

- H. Bottemanne et L. Joly, La dépression au féminin, Éditions du rocher, 2024.

- Canonico et al., Hormone therapy and venous thromboembolism among postmenopausal women: impact of the route of estrogen administration and progestogens: the ESTHER study, Circulation, 2007.

- Le Noan-Lainé et al., Characteristics of reproductive history, use of exogenous hormones and walking speed among women: Data from the CONSTANCES French Cohort Study, Maturitas, 2023.

This article was originally published in L'Édition n°26.

Find out more about the journal in digital version here.

For more articles and topics, subscribe to L'Édition and receive future issues: