Increase encouragement for open science - L'Edition 13 (june 2020)

(Article from L'Edition N°13 - june 2020)

Université Paris-Saclay is undertaking increasing initiatives to promote open science. At the core of national, European and international measures, the University defines its political position.

“Science is a common good that should be shared as widely as possible,” declared Frederique Vidal, Minister for Higher Education, Research and Innovation, in his opening speech about the national plan for open science on 4 July, 2018. The Ministry’s public policy plan echoes the digital republic bill passed on 7 October, 2016. It reaffirms the need to extend open communication of scientific research results in articles, books and data, and to ensure there are no difficulties, delays or costs related to their distribution.

What is the purpose? The editorial system has become incoherent. Researchers publish their articles in peer-reviewed journals, but the cost of access to their peers’ publications is increasingly expensive for their institutions, despite it being provided and assessed free of charge. This elitist system, run by a couple of large publishers who own most – and the most prestigious – of the journals, holds the public captive. A rogue system, it privatises knowledge produced with public funds, hitting institutions with prohibitive subscriptions and creating inequalities. For example, Université Paris-Saclay will spend €2M on subscription fees in 2020. The subscription for Elsevier alone is €700K. The University has chosen to cancel its Springer subscription since 2018.

To correct this situation, open science principles have been driving initiatives and strategies for action at institutional, national and European levels over the last few years. As Frederique Vidal announced: “France is committed to making open science daily practice for researchers by default.” The French plan aims to generalise open access to publications, whether in open access magazines or parallel to traditional magazines in open archive systems such as the HAL platform operated by the CNRS or ArXiv operated by Cornell University in the United States.

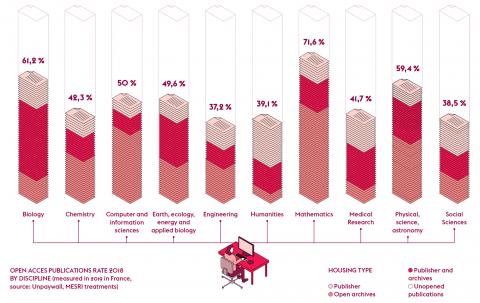

Article 30 of the 2016 law gives authors new rights which change the game. When at least 50% of research is government funded, authors are entitled to make their work available in an open archive after publication by the publisher: after six months for technical and medical sciences, and after twelve months for social sciences and humanities. “In the event that the contract with the publisher stipulates the contrary, it is deemed to be null and void,” adds ministry expert Marin Dacos, scientific advisor for open science to the head of the French department for research and innovation. Result: in 2019, 49% of French research publications were published with open access. This figure grows each year, though there remain disparities between disciplines.

All publications with open access in the future

Paris-Saclay is following the movement, defining its own guidelines on the subject in accordance with the national framework and national, European and international networks. Sylvie Retailleau, President of Université Paris-Saclay explains, “We now have to take a political stance. In 2020, our open science charter will be reinforced to increase encouragement for publication on open access platforms. Our approach is sufficiently developed for us to judge which are the best platforms, provide tools for researchers, and reflect on how to promote people who are committed to open science, for example with recruitment or promotion. The first measures will probably be applied in 2021, after discussion and vote at the University’s academic council.”

Etienne Augé, recently appointed Deputy Vice-President for Open Science at Université Paris-Saclay, confirms, “Major efforts are still required to educate and raise awareness among researchers, and from PhD level, and to put in place training pertinent to each discipline. But generally, everyone wants to do the right thing.” “A number of actions have been developed for this purpose including practical information sheets, courses and study days,” comments Julien Sempéré, prefigurator for the department in charge of libraries at Université Paris- Saclay that is actively driving this approach. “We are also developing a table of expected skills and producing educational videos addressing questions such as What is an open archive? and What is a predatory editor?.”

In 2018, 7,241 or 47% of the 15,133 publications signed by Université Paris-Saclay researchers were published on open access platforms. “Publishing research with open access does not jeopardise your research. It shows what you are working on,” explains Julien Sempéré. “In some cases, researchers hesitate to publish on open access platforms because they are convinced that publisher rights prevail over national law. They need more reassurance about the issue.”

Paris-Saclay has its own collection on the HAL platform where a large part of the University’s production is hosted. The objective is now to improve the user experience for researchers, “by displaying publications in a suitable user interface for example. We plan to help them to publish on open access platforms and make their lives easier,” says Julien Sempéré. In addition to HAL, the University also promotes other platforms delivering publications with a virtuous economic model, such as DOAJ (Directory of Open Access Journals), ArXiv, and OpenEdition.

Data with value

All research produces data - “the raw material of knowledge”, points out Frederique Vidal. Data is the second main focus of France’s plan for open science. “Sharing data opens up new scientific perspectives.” To that end, article 6 of the digital republic law opens all institutional data by default, including data from completed research. “Public institutions – universities and research centres – now have a new obligation regarding data because if researchers own their papers, the research data belongs to their employers. Institutions must take advantage of this new legal reality!” says Marin Dacos.

At Université Paris-Saclay, reflection is underway but “the application of clear measures will take more time than publications,” says Sylvie Retailleau. “First, we need to develop backup policies, initiate technical work, and facilitate understanding of what open science represents for research data.” The desire to make data openly available requires some restrictions. Certain data – personal, financial, medical, defence – must remain inaccessible. “It is rarely the obstacle. Due to a lack of awareness and global effort within the research community, we have not dared to share data that could have been,” Sempéré highlights.

Ensuring good data management

To this end, research projects funded by the European Commission and the French National Research Agency (ANR) must now include a data management plan. “A data management plan indicates what types of research data will be retrieved, their forms and intended use,”says Augé.

Good data management has many advantages: when data is placed in storage it is visible and can be referenced like scientific publications. “Making data accessible is also a sign of confidence in research results,” continues Etienne Augé. Marin Dacos adds, “Science is cumulative. Closed research efforts are in danger of being repetitive, resulting in wasted financial resources and loss of innovation. After all, the researcher is the main beneficiary. By storing his or her data, he or she ensures it is preserved correctly and facilitates its reuse.”

Producing metadata

Université Paris-Saclay produces an extraordinarily diverse range of data including instrumentation, archives and imagery. “As a result, it is very complex to have an overall vision. That requires collective action,” says Sempéré. Currently only 38 or 10% of the 400 H2020 projects – completed or not – carried out by University researchers and supported by the ANR have been published for open access.

“The practice is slowly becoming accepted procedure but there is one significant obstacle: organising and indexing data properly – in other words producing metadata – is time-consuming,” explains Sempéré. For example, with Christine Hatte, researcher at the Laboratory for climate and environmental sciences (LSCE - Université Paris-Saclay, UVSQ, CNRS, CEA), we are developing precise vocabulary for describing loess, the sediment deposited by wind during glacial periods. If a sample is to be used by other researchers, the conditions and context of its collection and storage must be correctly listed, such as weather conditions on the day, surrounding material, magnetic orientation of the face, how the face was prepared and cleaned, the temperature and drying time after the selection of samples.”

Another challenge for data is storage and processing. The University has used a facility on the Orsay campus for several years: Virtual Data. It hosts data submitted by researchers locally and free of charge. “We are now planning to pool other IT resources on a larger scale and test a cloud system,” says Augé.

Moving towards more citizen participation

Citizen science, the final component of the government’s plan for open science, is strongly supported by Paris-Saclay. “The University is very active in this area, notably through Diagonale Paris-Saclay, which invites citizens to reflect and debate about key societal issues. We are also working with M.I.S.S. – the House for Scientific Initiation and Awareness-raising – to develop scientific culture in schools, an ’in the trenches’ approach which adds purpose for citizens. This is also reflected in teaching provided to students, as university professors address ethical issues such as integrity, gender equality and sustainable development,” explains Sylvie Retailleau.

Citizen science also includes the participation of citizens in large-scale scientific projects that require a motivated workforce to carry out tasks that do not require specific scientific knowledge. “Participatory science is a way to produce first-rate knowledge about difficult subjects, and it helps to interest the general public in science. It is important to communicate with these people and develop dedicated tools to recognise the value of their work,” says Etienne Augé.

On 30 April, 2020, Université Paris-Saclay responded to the first call for a project funded by France’s open science fund and with a total budget of €2M. “We have applied to fund the development of the Bibliolabs platform. We also applied with Pssst magazine! (Paris- Saclay Sciences and Society) and proposed the creation of the annals for the Institut Pascal,” reports Etienne Augé. Result are expected in October 2020.

Références :

∙ www.ouvrirlascience.fr/open-science/

∙ www.universite-paris-saclay.fr/recherche/science-ouverte

∙www.youtube.com/watch?v=1IOnCEh34Nc&list=PLyeHq-UkjFkUIwwTZO4BS39qP-lmIlOna&index=18&t=0s