Endometriosis: the great unknown

This article can also be found on the issue of L'Édition (N. 20).

Endometriosis affects approximately 200 million women worldwide, has been described since ancient times and can cause debilitating daily pain and infertility. However, this disease remains largely unknown, both by scientists and the general public. Researchers are now trying to bring endometriosis out of the shadows.

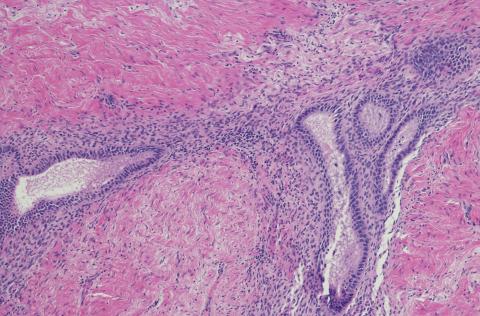

Today, it is estimated that endometriosis affects one in ten women of childbearing age (from the first menstrual period until menopause), i.e. about 1.5 million women in France, according to the Ministry of Health, and almost 200 million worldwide, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). This disease is related to the endometrium, the mucous membrane covering the inner lining of the body of the uterus. Endometriosis is characterised by the extrauterine presence of endometrial-like tissue. Recurrent and often disabling pain is its main symptom – whether felt during menstruation (dysmenorrhea), sexual inter-course (dyspareunia) or defecation (dyschezia) – located in the pelvic or abdominal area.

Infertility, digestive and urinary disorders during menstruation period and chronic fatigue may also occur. Although it was not until 1860 that Austrian pathologist Karel Rokitansky first used the term endometrio sis, the symptoms of the disease have been described for nearly 4,000 years, including in ancient Egypt.

However, endometriosis is still not well known. Marina Kvaskoff, an epidemiologist in the Exposome, Heredity, Cancer and Health team at the Centre for Research in Epidemiology and Population Health (CESP – Univ. Paris-Saclay, UVSQ, Inserm) is working to combat this fact. The researcher is the scientific manager and President of the Scientific Council of the ComPaRe-Endometriose cohort study of Assistance publique – Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), President of the Scientific Council of the French Endometriosis Research Foundation and co-leader of the “research” working group of the national strategy to fight endometriosis. “It is said that endometriosis affects one in ten women, but this is a very rough figure which requires clarification. Part of my work involves trying to better understand the heterogeneity of the disease, its different forms. Today, beyond the short definition we have of the disease, there are many basic questions to which we have no answers,” she says. “What are the risk factors for this disease? Does the environment influence the risk of developing it? What is the role of genetics, and which genes in particular? How does the disease evolve over time? When and how does it start?”

What we know about endometriosis

When menstruation starts, the endometrium is naturally eliminated. In women with endometrio sis, altered endometrial tissue becomes implanted in the pelvic cavity outside the uterus. The disease is classified according to four macrophenotypes. When the lesions do not exceed a few millimetres in diameter, the en dometriosis is said to be superficial or peritoneal. If the lesions are larger than five millimetres and deeply embedded under the peritoneum, the membrane covering the entire abdominal cavity, it is called deep en dometriosis. Endometriotic cysts can also appear on the ovaries and are called endometrio mas. Lastly, extra-pelvic endometriosis describes the appearance of lesions typical of the disease in organs far from the uterus, such as the diaphragm, or less frequently lungs and even the brain. “However, and this is quite disturbing, the existing stages of the disease are not correlated with the symptoms,” warns Marina Kvaskoff. “A woman with deep endometriosis may be asymptomatic while a patient may suffer greatly from superficial endometriosis. ”

Another notable fact is that endometriosis is a hormone-dependent disease. Lesions proliferate in the presence of oestrogen, which is produced in huge quantities during menstruation. Suppressing menstruation, through the contraceptive pill, is therefore one of the treatments offered for endometriosis. “The pill is the first-line drug treatment,” explains Marina Kvaskoff. Surgery is also possible, to remove the lesions. “Unfortunately, lesions may return in some patients after surgery. There are different routes and surgery can be life-saving or may not work at all, or even make the situation worse. There appears to be a recurrence of lesions and pain in some cases,” adds the researcher

There are four main theories to explain the pathogenesis of endometriosis. The reflux theory, known as retrograde menstruation, is the most commonly described. This hypothesis is based on the idea that during menstrual cycles, menstrual flow occurs through the fallopian tubes, which connect the ovaries to the uterus. The endometrial tissue then implants in the pelvic cavity. However, this theory does not explain all cases of endometriosis, and other hypotheses exist. The in-situ theory, for example, by attributing an embryonic origin to the disease, explains why en dometriosis affects some women with Rokitansky syndrome (absence of uterus and fallopian tubes), some women before their first period, and some men. On the other hand, this theory implies a uniform distribution of lesions in the peritoneum; however, observations show that lesions are more often concentrated on the left side. The lymphovascular theory suggests that endometrial cells use lymphatic and vascular channels, like metastases, to travel to ectopic sites. “While this theory perfectly explains cases of extra-pelvic endometriosis, it does not explain the other cases of the disease,” comments Marina Kvaskoff. Lastly, stem cell theory explains the cases of endometriosis observed in infants and in particular the presence of vaginal bleeding in newborns. “Practically speaking, no single theory explains every case of endometriosis observed to date. It is even possible that several occur in the same individual!” adds the researcher.

Listening to patients is the cornerstone of diagnosis

“In terms of diagnosing the disease, there are no validated biomarkers for endometriosis. The reference means of detection remains imaging: endovaginal ultrasound and MRI of the lower part of the pelvis,” continues the epidemiologist. “The problem is that not enough radiologists are sufficiently trained to detect the lesions, which may be almost invisible to the non-expert eye. We need better diagnostic tools, but we also need to listen to patients better.”

Questionnaires have a major role to play in the management and diagnosis of endometriosis. Arnaud Fauconnier is Director of the Clinical Risks and Safety in Women’s and Perinatal Health Laboratory (RISCQ – Univ. Paris-Saclay, UVSQ). His work focuses in particular on tools for measuring diagnosis and quality of life for patients. Arnaud Fauconnier, an obstetrician-gynaecologist by training, is also behind Endocap, a research programme on endometriosis, the measurement of patients’ quality of life and the disability that the disease represents for them. “An endometriosis diagnosis is extremely difficult, because it is a disease that can be invisible during routine gynaecological examinations,” explains the gynaecologist. The programme is based on a database of nearly 1,000 patients with en dometriosis. A questionnaire, called ENDOL-4D, which is filled out independently by candidates, is used to measure their symptoms and the alteration in their quality of life.

The Community of Patients for Research (ComPaRe) is a cohort of patients with different chronic diseases who agree to participate in research into these diseases using questionnaires. The endometriosis subcohort was launched in 2019. Study coordinator Marina Kvaskoff praises the importance of this participatory model in research: “Patients are involved in the research by contributing to ComPaRe-Endometriosis and answering questionnaires about their disease, their daily life and their suffering.” More than 10,000 patients have participated in the study to date, and initial results regarding patients’ perspectives on improving their management have recently been published.

A terrifying and unacceptable diagnostic error

In addition to the questions about the pathogen esis and detection tools for endometriosis, the erroneous diagnosis of this disease is also a major problem. According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the average time between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis is between seven and ten years. “Most women with the disease have been to the doctor around five times before getting the correct diagnosis. This diagnostic error is terrifying and unacceptable,” laments Arnaud Fauconnier.

“How can we explain this huge delay?” asks Marina Kvaskoff. “We are facing several problems. On the one hand, the trivialisation of symptoms. Women who experience pain during menstruation are usually not immediately concerned, and unfortunately neither are those around them or medical personnel. In ComPaRe-Endometriose, there are many testimonies from patients who report that a lot of doctors simply miss the symptoms, due to a lack of training, or simply say ‘It’s all in your mind’. There is a lack of training that could enable health professionals to recognise the disease.”

This period of error adds suffering to patients and also results in a methodological headache for the scientific community. “All the studies conducted so far focus on endometriosis diagnosis. Lastly, it is complex to work on the risk of endometriosis or on the beginnings of the disease because very often the cases of en dometriosis that we observe have been diagnosed and the patients have carried the disease for several years,” notes Marina Kvaskoff.

In short, this is a disease that has been described for four millennia and for which neither the causes, the forms nor the means of diagnosis are known with certainty. For Marina Kvaskoff, it is anything but a coincidence that endometriosis research lacks resources, when the disease only affects women. “Current data show that research into specifically male conditions is much better funded than research focusing on female conditions. Endometriosis is a glaring example of gender bias in research.”

Publications :

- Fauconnier A. et al. Early identification of women with endometriosis by means of a simple patient-completed questionnaire screening tool: a diagnostic study, Fertility and Sterility, 116 (6), 2021.

- Gouesbet S. et al. Patients’ perspectives on how to improve the management of endometriosis: a citizen science study within the ComPaRe-Endometriosis e-cohort. J Wom Health, 2022.

- Gouesbet S. et al. Patients' Perspectives on How to Improve Endometriosis Care: A Large Qualitative Study Within the ComPaRe-Endometriosis e-Cohort. J Wom Health. 2023.

- Mirin AA. Gender Disparity in the Funding of Diseases by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. J Wom Health. 2021.

- Rosenbaum J. et al. Des pistes de réflexion pour la recherche sur l’endométriose en France. Med Sci (Paris), 38 (3), 2022.