Aurélien Marabelle: using the immune system as a therapeutic tool to treat cancer

Aurélien Marabelle is a medical oncologist and professor at Université Paris-Saclay. He is head of the Laboratory of Translational Research in Immunotherapy (LRTI) within the Tumour Immunology and anti-cancer immunotherapy unit (ITIC - Univ. Paris-Saclay/French National Institute of Health and Medical Research, Inserm/Gustave Roussy). Recognised as a (ITIC – Univ. Paris-Saclay/Inserm/Gustave Roussy). Distingué en 2023 en tant que Highly Cited Researcher in 2023, his practice is devoted to early-phase clinical trials of cancer immunotherapies.

Aurélien Marabelle's interest in medicine was sparked by a chance internship with Dr Éric Bérard in a hospital on the outskirts of Lyon, undertaken while in year 11 at school. "Having grown up in quite a privileged environment, here I was confronted with a very intense world, particularly during a consultation with a young quadriplegic my own age," he recalls. With his baccalaureate in hand, however, he chose not to start medical school straight away. "I wanted to maintain the balance between mathematics, biology and the hard sciences in my learning for a few more years," explains the researcher.

He then enrolled in a 2-year preparatory course for a competitive exam in science, entered the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) Lyon, obtained a master's degree in physiology which took him to King's College London for a semester, and finally, in 1999, took a conversion course which enabled him to join the medical course in 3rd year. "It was then that I embarked on an exciting adventure which, through internships and meeting people, and moving from Paris to Lyon, via Clermont-Ferrand and Stanford, would eventually lead me to Gustave Roussy," says Aurélien Marabelle.

One initial driving force: conducting research at the patient's bedside

Like any research career, Aurélien Marabelle's path has been built around a number of highlights, and at the top of the list are his internship in paediatrics at Clermont-Ferrand and his first internship in paediatric oncology. "More than paediatrics in itself, it was the idea of conducting research at the patient's bedside that motivated my choice of internship. It's a choice I've never regretted, as it led me to treat two patient cases that were decisive in my subsequent research," explains the oncologist.

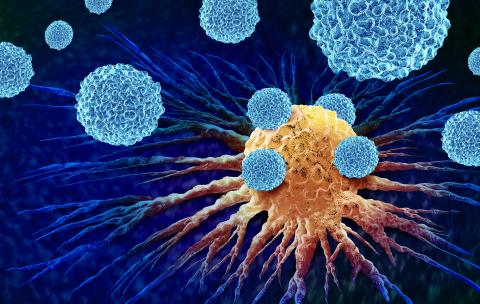

The first case involved a twelve-year-old girl suffering from two types of cancer (neuroblastoma and myeloid leukaemia), who was cured with a bone marrow allograft that produced a graft reaction against both cancers. "That was when I became aware of the immune system's power in fighting cancer." The second case was a baby with IPEX syndrome, a generalised autoimmune disease characterised by a lack of immune tolerance. "Monitoring this baby made me grasp the power of the immune system in its toxicity, especially against healthy tissue, when dysregulated, and helped me understand how key regulatory T cells are in regulating the immune response." These were challenging years, but they helped Aurélien Marabelle in defining his objective: to work on cancer immunotherapy.

One objective: supporting the immunotherapy revolution

With this new objective in mind, Aurélien Marabelle decided, during his internship, to do a DEA (today's equivalent being a 2nd year Master's research degree) in immunology, with a focus on immunotherapy. He met Prof. Raphaël Rousseau, a Frenchman developing anti-neuroblastoma cellular immunotherapies called CAR-T Cells in Houston, USA. "It was in 2005, at a time when there was very little research into cancer immunotherapy. That's why, when Raphaël asked me to join him in Lyon, I didn't hesitate for a second and set off to finish my paediatric internship with him, followed by two years as an assistant developing anti-leukaemia CAR-T Cells." »

This research, carried out as part of a European consortium, was met with unexpected resistance from their French colleagues at the time, and led to Prof. Rousseau's departure for the pharmaceutical industry. "When I had the opportunity in 2009, I went to Stanford University in California as a post-doc in a team working on immunomodulatory antibodies. I spent three extraordinary years there, fully involved in the immunotherapy revolution that was in full swing across the Atlantic." »

The researcher's enthusiasm was somewhat dampened when, returning to Lyon as a hospital practitioner in 2012, he realised that he wouldn't get much support to pursue his immunotherapy research. It was then that he began what he describes as "crossing the desert", until he met Prof. Jean-Charles Soria, then head of the Department of Therapeutic Innovation and Early Stage Trials (DITEP) at Gustave Roussy, and Prof. Alexander Eggermont, General Director of the institute, in 2014. "Everything was perfectly aligned, so I moved to Gustave Roussy where, for ten years now, I've been developing clinical and translational research in cancer immunotherapy, in the specific context of early-phase clinical trials to develop new drugs." ».

One method: translational research

After arriving at Gustave Roussy, Aurélien Marabelle set up a laboratory of translational research in immunotherapy (LRTI), which he now manages. "Our aim is to better understand resistance to immunotherapy – why some patients, around one in five, respond magnificently to immunotherapy or are even cured of their metastatic cancer, while others don't – and to develop new drugs to better treat patients earlier in the progression of the disease. To achieve this, our approach is to use patient samples to try and understand what happens before and during immunotherapy, or conversely, to use the results of our research to come back to the patient with new drugs and clinical trials," explains the oncologist.

REMISSION: towards more personalised treatments

This ambition is being materialised through the REMISSION research programme, supported by the France 2030 Investments for the Future programme. Led by Aurélien Marabelle, this programme aims to use fresh tissue (whole blood, tumour biopsy) as a source of biomarkers to adapt new immunotherapy strategies to the biology of patients and their cancer. "It's important to note that, in nearly 95% of clinical trials, patients are treated blindly, without knowing whether or not they express the drug target, even though we have targeted therapies. This problem is explained in part by the poor predictive value and the multiple weeks required for the analysis of frozen or fixed tissues used routinely, preventing personalised patient care," Aurélien Marabelle explains. That's what REMISSION promises to change, thanks to an innovation developed by LRTI that enables us to work routinely on fresh samples, generate data in just a few hours and deliver sensitive, specific results. "We hope to accelerate clinical research by opening up new cohorts, and achieve more personalised treatments," concludes Aurélien Marabelle.