Shell construction by physical self-organization and cell sensorial activity: the case of the cephalopod Argonauta

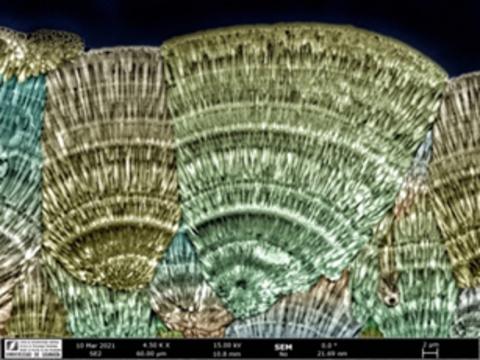

The female cephalopod Argonauta secretes a shell with its dorsal arms, being thus non-homologous to the molluscan shell1. It consists of two layers of fibers that grow and elongate perpendicular to the outer and inner surfaces2,3. Each fiber has a high-Mg calcitic core sheathed by extremely thin organic membranes3,4. These conform a polygonal (cellular) network in cross-section1. During growth, fibers with small cross-sectional areas tend to shrink, whereas those with large sections tend to widen. In this way, they follow the von Neumann-Mullins law5,6. Based on this behavior, we hypothesize that fibers evolve as an emulsion between the fluid precursors of both the calcite and organic phases. In addition, when polygons reach big cross-sectional areas, they become subdivided by new membranes. In this way, the size distribution of the organic polygons remains constant throughout growth. The only way to interpret this partitioning process is by inferring that the living cells from the mineralizing tissue are able to ‘locate’ particularly large polygons and subdivide them. To do this, living cells must perform contact recognition and subsequent secretion at sub-micron scale. Accordingly, the fabrication of the argonaut shell proceeds by physical self-organization together with direct cellular activity.

Sorbonne Université - Faculté des Sciences et Ingénierie Campus Pierre et Marie Curie 4 place Jussieu 75005 ParisThe female cephalopod Argonauta secretes a shell with its dorsal arms, being thus non-homologous to the molluscan shell1. It consists of two layers of fibers that grow and elongate perpendicular to the outer and inner surfaces2,3. Each fiber has a high-Mg calcitic core sheathed by extremely thin organic membranes3,4. These conform a polygonal (cellular) network in cross-section1. During growth, fibers with small cross-sectional areas tend to shrink, whereas those with large sections tend to widen. In this way, they follow the von Neumann-Mullins law5,6. Based on this behavior, we hypothesize that fibers evolve as an emulsion between the fluid precursors of both the calcite and organic phases. In addition, when polygons reach big cross-sectional areas, they become subdivided by new membranes. In this way, the size distribution of the organic polygons remains constant throughout growth. The only way to interpret this partitioning process is by inferring that the living cells from the mineralizing tissue are able to ‘locate’ particularly large polygons and subdivide them. To do this, living cells must perform contact recognition and subsequent secretion at sub-micron scale. Accordingly, the fabrication of the argonaut shell proceeds by physical self-organization together with direct cellular activity.